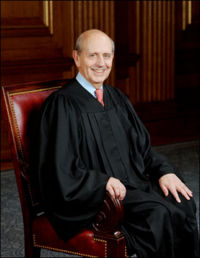

Stephen Breyer

Stephen Gerald Breyer (born August 15, 1938) is an American attorney, political figure, and jurist. Since 1994 he has served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Known for his pragmatic approach to constitutional law, Breyer often sides with the liberal wing of the Court.

Early life and education

Breyer was born to a middle-class Jewish family in San Francisco, California, on August 15, 1938. At age 12, he was awarded Eagle Scout. In 1955, Breyer graduated from Lowell High School. At Lowell, he was a member of the Lowell Forensic Society and debated regularly in high school debate tournaments, including against future Harvard Law School professor Lawrence Tribe.

After graduating from Lowell, Breyer went on to receive a Bachelor of Arts in philosophy from Stanford University, a Bachelor of Arts from Magdalen College at the University of Oxford as a Marshall Scholar, and a Bachelor of Laws (LL.B) from Harvard Law School. Breyer is the older brother of federal district judge Charles Breyer.

In 1967, he married Joanna Freda Hare, a psychologist and member of the British aristocracy (the youngest daughter of John Hare, 1st Viscount Blakenham). The Breyers have three grown children, Chloe (an Episcopal priest, and author of The Close), Nell, and Michael.

Legal career

Breyer served as a law clerk to Associate Justice Arthur Goldberg during the 1964 term. He was a special assistant to the Assistant U.S. Attorney General for Antitrust from 1965 to 1967 and an assistant special prosecutor on the Watergate Special Prosecution Force in 1973. Breyer was a special counsel to the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary from 1974 to 1975 and served as chief counsel of the committee from 1979 to 1980. He worked closely with the chairman of the committee, Senator Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts, and helped pass airline deregulation legislation in the United States that closed the Civil Aeronautics Board.

Breyer became an assistant professor, law professor, and lecturer at Harvard Law School starting in 1967. Breyer taught at Harvard Law School until 1994, also serving as a professor at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government from 1977 to 1980. At Harvard, Breyer was known as a leading expert on administrative law. While there, he authored two highly influential books on deregulation: Breaking the Vicious Circle: Toward Effective Risk Regulation and Regulation and Its Reform. Both remain extremely important in the law of administration and bureaucracies. Breyer was a visiting professor at the College of Law in Sydney, Australia, and later at the University of Rome.

Judicial career

From 1980 to 1994, Breyer served as a Judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit and as its Chief Judge from 1990 to 1994. His nomination to the Court of Appeals was the last judgeship approved by the Senate in the Carter administration. He also served as a member of the Judicial Conference of the United States between 1990 and 1994 and the United States Sentencing Commission between 1985 and 1989. On the sentencing commission, Breyer played a key role in reforming federal criminal sentencing procedures, producing the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, which were formulated to increase uniformity in sentences for criminal cases.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton considered him for the seat that ultimately went to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Clinton nominated him as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court on May 17, 1994, to fill the vacancy left after the retirement of Harry Blackmun in 1994. Breyer was confirmed by the U.S. Senate in an 87 to 9 vote and took his seat August 3, 1994.

Breyer was also the second longest-serving "junior justice" in the history of the Court, close to surpassing the record set by Justice Joseph Story of 4,228 days (from February 3, 1812 to September 1, 1823); Breyer fell 29 days short of tying this record, which he would have reached on March 1, 2006, had Justice Samuel Alito not joined the Court on January 31, 2006. Although Chief Justice Roberts joined the Court in September of 2005, the duties of the junior Justice never fall upon the Chief Justice, who is considered primus inter paresófirst among equals.

Judicial philosophy

In general

On the bench, Breyer generally takes a pragmatic approach to constitutional issues, interested more in producing coherence and continuity in the law than in following doctrinal, historical or textual strictures. He has said that while some of his colleagues "emphasize language, a more literal reading of the text, history and tradition," he prefers to consider the "purpose and consequences" of the text.[2]

While somewhat moderate, Breyer most frequently sides with Justices John Paul Stevens, David Souter and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, generally acknowledged as being the "liberal" wing of the court. He has consistently voted in favor of abortion rights, one of the most controversial areas of the Supreme Court's docket. He has also urged that the Supreme Court cite international law as persuasive (but not binding) authority in its decisions. However, Breyer is also deferential to the interests of law enforcement and urges that the Court be deferential to legislative judgments in its First Amendment rulings. Breyer has also demonstrated a consistent pattern of deference to Congress, voting to overturn congressional legislation at a lower rate than any other Supreme Court justice since 1994.

Active Liberty

Breyer's recent book, Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution, deals with his judicial philosophy at greater length, emphasizing his belief in judicial deference to democratic decision-making.

Breyer argues that the Framers of the Constitution set out to establish a democratic government involving the maximum liberty for its citizens. But what is liberty? Breyer refers the reader to Isaiah Berlinís Two Concepts of Liberty. The first Berlinian concept, being what most people understand by liberty, is "freedom from government coercion;" Berlin termed this negative liberty and warned against its diminution. Breyer terms this "modern liberty." The second Berlinian concept ó to Berlin, "positive liberty" - is the "freedom to participate in the government;" In Breyer's terminology, this is the titular "active liberty," which he believes the Judge should champion. Having established this premise of what liberty is, and argued that the Framers intended to maximize active liberty over the modern liberty, Breyer argues a predominantly Utilitarian case for Judges making rulings which give effect to the democratic intentions of the Constitution.

However, both books' historical premises and practical prescriptions have been challenged, for example, by Prof. Peter Berkowitz's Democratizing The Constitution. According to Berkowitz, "The reason that 'The primarily democratic nature of the Constitutionís governmental structure has not always seemed obvious' ," as Breyer puts it, is "because itís not true, at least in Breyerís sense that the Constitution elevates active liberty above modern [negative] liberty." Breyer "demonstrates not fidelity to the Constitution, but rather a determination to rewrite the Constitutionís priorities," and in any eventuality, throws his "Active Liberty" theory overboard where abortion is concerned, "prefer[ing] judicial decisions that protect womenís modern liberty, which remove controversial issues from democratic discourse." In a book which never rises to answer the textualist charge that the Living Documentarian Judge is a law unto himself, Active Liberty "suggests that when necessary, instead of choosing the consequence that serves what he regards as the Constitutionís leading purpose, Breyer will determine the Constitutionís leading purpose on the basis of the consequence that he prefers to vindicate."

In a New Yorker article in October, 2005, "Breyer concedes that a judicial approach based on 'active liberty' will not yield solutions to every constitutional debate. 'Respecting the democratic process does not mean you abdicate your role of enforcing the limits in the Constitution, whether in the Bill of Rights or in separation of powers,' he said. 'We have to decide when these limits are exceeded. People tend to forget that when the limits are not exceeded. Almost everything the government does is within these limits. We have to give guidance. There is no absolute guidance, no absolute rules.' "

To his point, and from a discussion at the New York Historical Society in March, 2006, Breyer has noted that "democratic means" did not bring about an end to slavery (the American Civil War did) or the concept of "one man, one vote," which allowed corrupt and discriminatory (but democratic-inspired) state laws to be overturned in favor of civil rights.

Writing style

Breyer is well-known for his personal writing style, in which he never uses footnotes in his opinions. He feels that keeping all citations in the text results in better, more readable writing as he is not tempted to use footnotes to expound on irrelevant points.